The paradox of success: Kahneman and Tversky's prospect theory

For some time now, I have been observing, especially among trader friends whose actions I have the opportunity to view up close, a certain paradox. I didn’t know what to call it, so I used the term “paradox of success.” Since I don’t want this post to be overly lengthy, I’ll get straight to the point.

It’s about situations where it is consistently much easier for us to hold losing positions than profitable ones. I’ve worked through this issue a long time ago. Of course, like everyone else, I make mistakes, sometimes very foolish ones, but my failures are never the result of combining holding onto losing positions and cutting profitable ones.

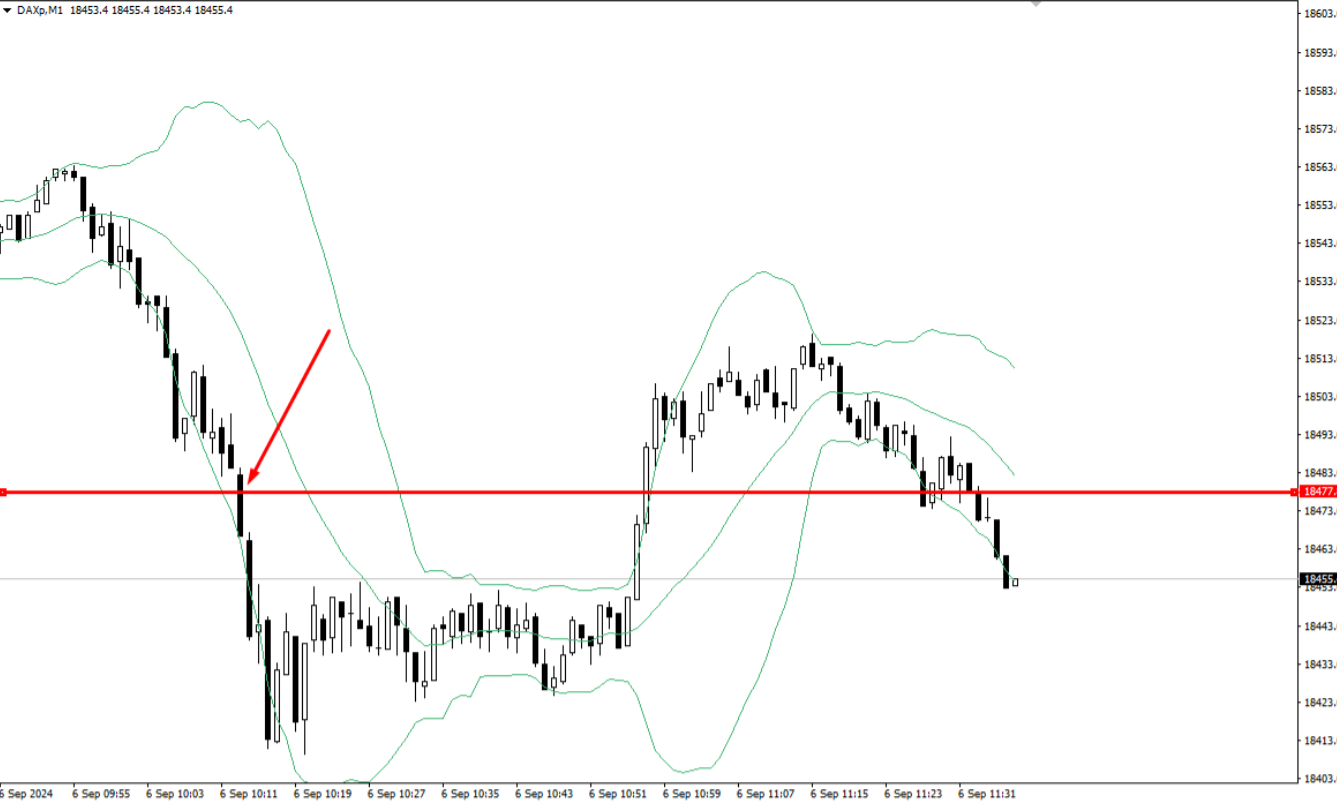

When I fight with the market, with the trend, and hold losing positions, it doesn’t come from the same reasons as it does for most people. However, when the market moves in my direction, I think I manage it quite well. An example of this would be yesterday’s DAX trade.

So, for many traders, this holding of losses, according to the Prospect Theory mentioned in the title by Kahneman and Tversky, stems from the fact that we feel losses more strongly than gains of the same magnitude. Paradoxically, when a position is profitable, the greater fear of potential loss motivates us to close the position faster than in a situation where the market moves against us, and there is hope for a reversal of the trend.

Personally, I have worked through this issue, and holding onto losses is not dictated by hope for a reversal but something much worse—but that is a topic for another occasion. Profits, on the other hand, I can hold onto.

Even today, in a discussion with a friend who executed trades perfectly according to the rules but cut profits very quickly, I tried to explain to him: what’s the point of taking the risk if these trades don’t have a chance to pay off? If, as soon as the price moves slightly in the opposite direction and then returns to the entry level, he closes the position.

While his behavior paid off in today’s session—because after the morning rally, the DAX lost steam for further growth, and his exits from long positions near the peaks turned out to be the best solution in hindsight—I am convinced that in the long term, this approach will not add up.

The topics of holding onto losses and profits are too broad to fit into one article, so in this one, I’d like to focus on holding onto profitable positions. In the future, we’ll reflect on holding onto losses.

One Key Issue in Holding Profitable Positions Is the Entry

I believe that the better the entry, the easier it is to manage the position later.

A trader whose position is entered at a level where the price hovers around the trade, moving into profit, then loss, then back into profit, etc., will handle it differently than a trader whose position quickly moves into profit after entry. It will be easier for the latter to hold, reduce, or somehow remove the risk from the position.

The most popular way to remove risk is to move the stop-loss order to breakeven (BE)—that is, the entry point. Personally, I prefer closing part of the position in such a way that the closed portion covers the potential loss on the original SL. However, to be honest, I usually try to play out the setup from start to finish, closing part only upon reaching the target. That doesn’t mean I don’t use partial closures in tight situations where I need to play more defensively.

Example: Managing Risk with Partial Closures

Let’s assume I’ve opened a sell position with an initial SL of 30 points.

If the price moves 30 points in the expected direction, closing half of the position—leaving the other half with the original SL—puts me at breakeven. Even if, after partially booking profits, the price returns to the entry point, the psychological comfort in such a situation is much greater than at the beginning.

At the beginning, my risk is 30 points. After booking half the position at +30 points, my risk is 0, even without moving the SL. You could, of course, move the remaining SL to BE; in that case, you’re not left empty-handed. However, I rarely do this.

The reason is straightforward: when the price returns to the entry point, I ask myself if something has changed. Has the price returning to the level where I sold invalidated my setup? Or has nothing changed?

If nothing has changed, the remaining half of the position stays with the original SL. If the situation seems even more attractive, I might reopen the closed half and reduce the SL to 15 points—in such a situation, the setup remains cost-free. However, if key elements that previously prompted me to sell are no longer valid, I am ready to close the remaining part of the position.

Especially on funded accounts, when during the verification phase we are trading on a demo account and practically have no profits from it, apart from potentially passing the verification process that we are striving for, it’s hard for me to understand cutting profitable positions.

Let me reiterate—this doesn’t apply to those who trade short moves, scalps, etc. This is about traders attempting to play intraday swings. Because if you can let a position go 100 points into the red when you’re wrong, but when you’re right, you book 10-20 points—you won’t convince me that this approach will work in the long term.

Now let’s assume that our short position has moved as expected and is now earning 150 points. How many times have you experienced a situation where, on a small price hesitation, you exited the position, only for the price to drop another 150 points immediately afterward?

If you haven’t booked partial profits or don’t tolerate the method of partial closures, it’s worth calmly analyzing the situation again (I turn off the position view on the chart for this, as it helps me conduct the analysis more objectively) and assessing to which level a correction would likely remain just a correction. If the price is highly unlikely to break below this level, you can secure the position just above it. If the profit at this point is satisfactory to you, you have a solid solution.

You need to develop a very strong belief that the money in an open position is just a number—it doesn’t matter—especially on verification accounts.

You should trade what the market is showing, not what the number next to your position is showing. If you’re trading what the market is showing, and you see the price dropping, struggling to bounce, then a 10-point bounce shouldn’t scare you.

Continuing on the topic of a bounce... I never close profitable positions when the price is dropping/rising—in other words, when it’s moving in the expected direction. Even if the price hits the target level—the level I planned to play the position to—I wait to see if there’s a reaction or not. If there is a reaction, I close. If there isn’t, the price very often moves 20-50 points beyond the target level.

And even on today’s session, the price hit the target level for my position, and within 4 minutes it moved 67 points beyond that level, where my target was 107 points.

It’s worth letting the market “breathe,” and I’m convinced that this approach compensates for the situations where the price hits our target level and immediately reverses, shaving off a few points from our profit.

Take a look at the chart above and see what the price did with my target level on the one-minute chart. What happened opens the door to my favorite approach for helping maintain profitable positions. In this case, it didn’t work because there was a significant bounce.

However, when the price moved 67 points beyond the target level, I could have secured the position at the target level using a stop-loss. In such a situation, the level I planned to play the position to becomes the level at which the position is secured—meaning what I aimed to achieve is already locked in, while simultaneously allowing the market to move further.

And situations like this are born from small actions—allowing the market to take a step, holding back from closing the position at the target level for a minute, two, or five.

I know that we all have predefined SL and TP levels, enter, set the SL, set the TP, and wait 😃. But the reality is entirely different.

Before the price hits the SL or TP, most of us will make a series of adjustments. Of course, there are those who actually trade this way with stoic calm—entry, SL, TP—and don’t even track what happens next. But let’s not kid ourselves—they are a definite minority. And we aim to reach the majority and encourage reflection.

So let’s separate emotions from our strategies and try to flow with the market.

Let’s compare this to a slot machine. It looks like we’ve hit some figure that pays very well—we’re collecting the payout. And these machines probably spit out 5 zloty coins (I know this because my boss in my first job years ago was a big fan of these machines; as a driver, I often had to wait until he spent a few hundred zloty—it happened that he won). So the machine is spitting out 5 zloty coins—do we wait until it stops spitting? Or do we walk away at a random moment with a handful of coins, leaving the machine to continue?

To sum up, a lot depends on perspective, and the perspective from which we will look at the position we hold depends on the actions and decisions we make in the initial phase of the trade.

An extremely important skill to develop is ignoring the result. Sometimes this has its downsides and allows us to take excessively large risks, which is why rigid rules are necessary. If I’m playing a well-calculated position, of a consistent size, and not adding to losers, I don’t need to worry about the result—I just need to execute the assumptions of the strategy.

It’s worse when we drift off course, and looking at the result brings fear.